The Forest Song: A history of ballet in Ukraine

A history of the development of ballet in Ukraine and its "national" ballet

“Oh joy! A star from heaven fell in my heart!” - Mavka. Act 1 of The Forest Song by Lesya Ukrainka (1912)

“A dense and hoary primeval forest in Volhynia. The scene is a spacious glade in the heart of the forest, dotted with willows and one very old oak… The spot is wild and mysterious but not gloomy, filled with the tender, pensive beauty of Polissye, the wooded part of Volhynia.” - These are some of the opening lines in the text of Lesya Ukrainka’s play The Forest Song, describing the wild, mysterious atmosphere of a mystical woodland glade in an enchanted forest in Volhynia, Ukraine.

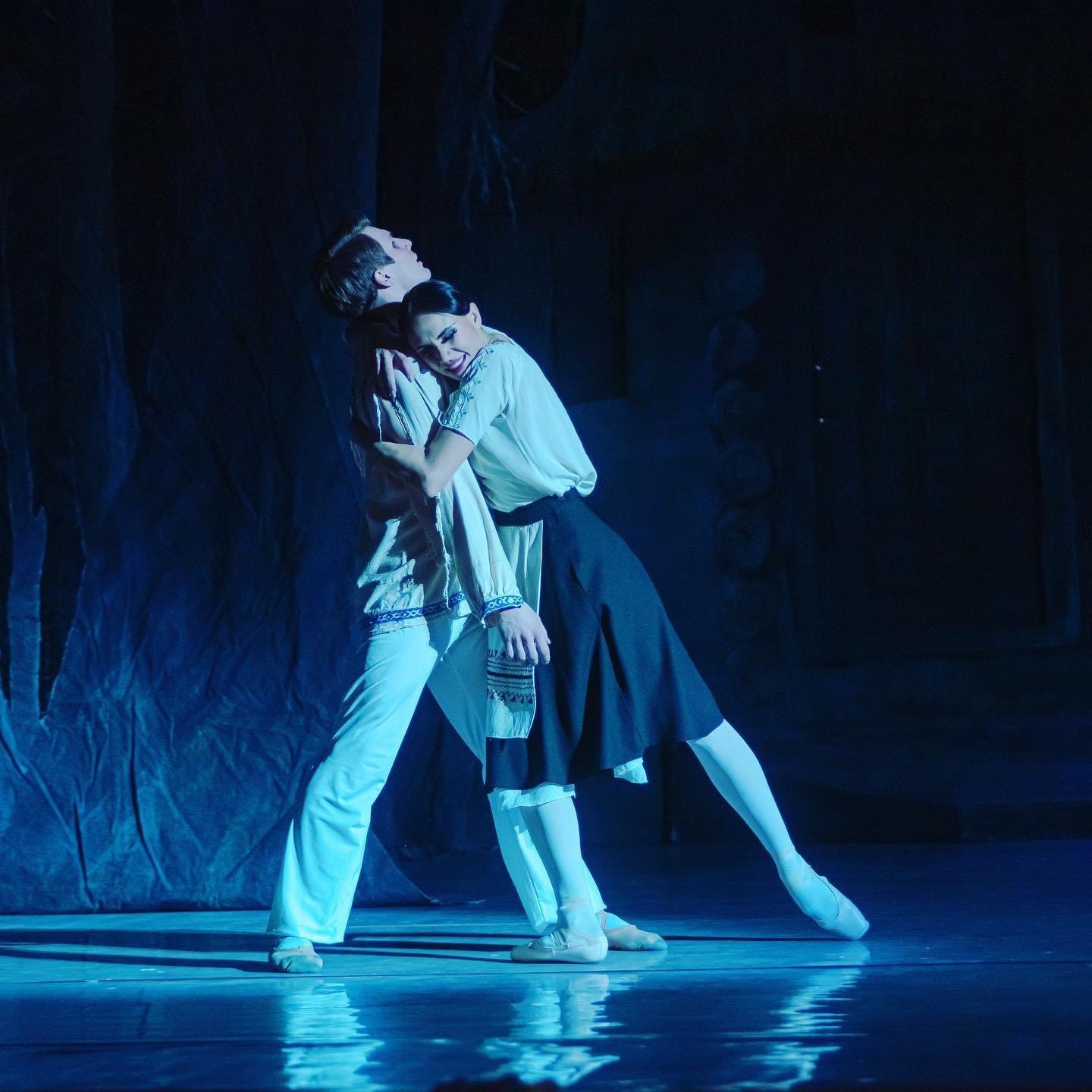

The Forest Song is one of the most iconic works in Ukrainian literature. Published in 1912 and first staged in 1918, it dives into the world of Slavic mythology and tells of a tragic love story between a young man and a forest nymph. In 1936, the play was adapted into a ballet and it remains one of the most beloved works in the Ukrainian ballet repertoire among artists and audiences alike. But for many years, this ballet was unknown of in the international ballet community. It is only now, after Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine three years ago, that The Forest Song has started to gain some more attention around the world.

When I started to learn more about the Ukrainian Ballet, as a ballet historian, I became curious to learn about its history and I started to do some research. However, researching this area has not been easy. The overriding reason is because there are no published sources that directly focus on the topic. There was a series of books written by Yuriy Stanishevsky about the history of theatre and ballet in Ukraine, but they are out of print and were never translated into English. On top of that, I was told that they are not reliable because they are a Soviet study that distorts the real Ukrainian history, which needs to be rewritten. If that is the case, it is my aim that this essay should be a step forward about the development of ballet in Ukraine.

In order to put a picture together, I turned to sources that look at the history of Ukraine in comparison to that of ballet in the Soviet Union and of artists who worked in Ukraine in the early 20th century. I also found on the website of the National Ballet Theatre of Ukraine a small introductory essay to The Forest Song by Maria Zagaykevych and online articles about Lesya Ukrainka. There are missing pieces, but there is enough to give an understanding. In this essay, I will look into the wider picture - a brief insight into the life and career of Lesya Ukrainka and her play, and ballet history after the 1917 Revolution up to the staging of The Forest Song.

“Oh Mavka dear, you’re drawing out my soul…” - Lukash. Act 1 of The Forest Song by Lesya Ukrainka (1912)

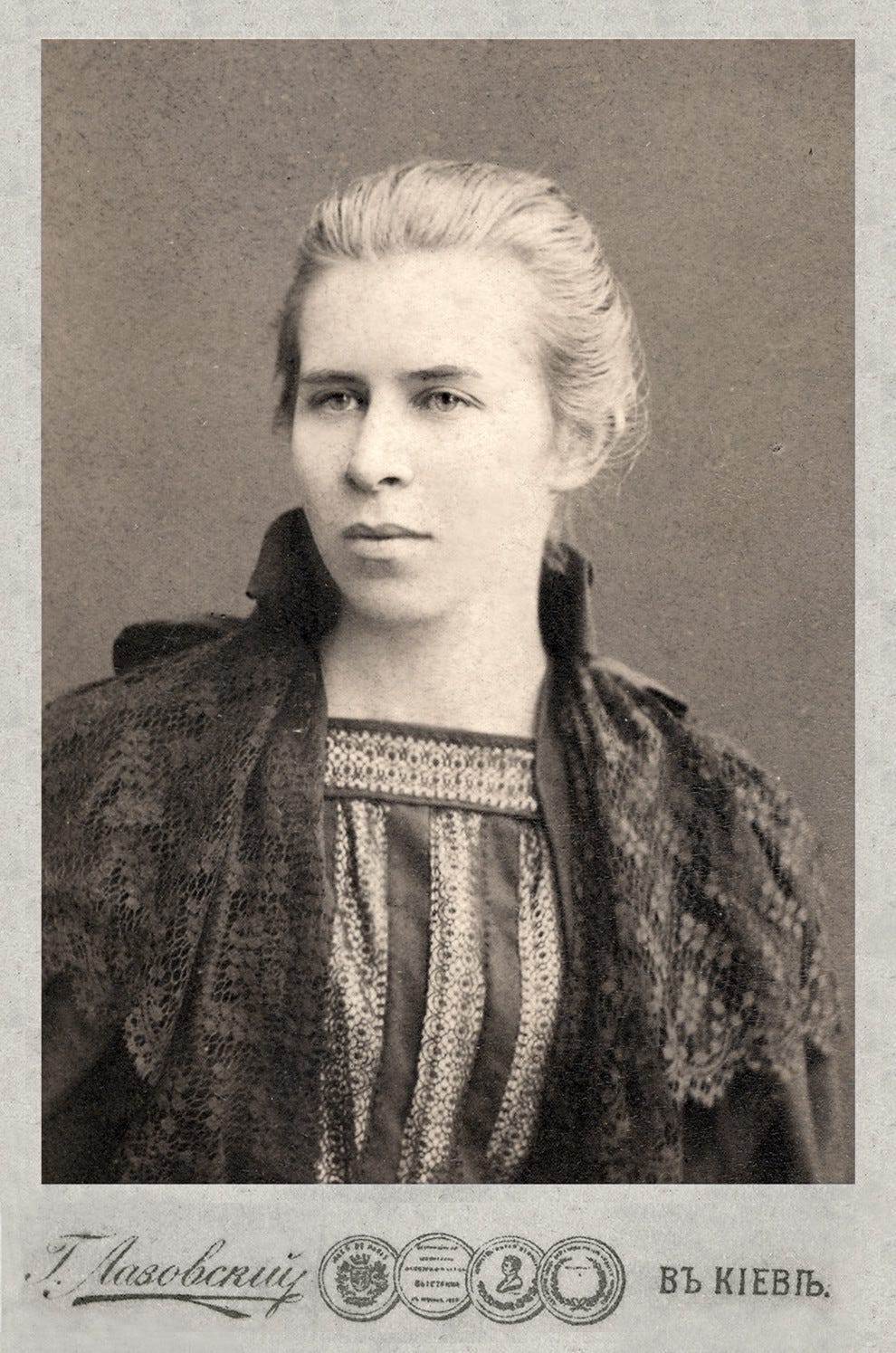

Lesya Ukrainka, one of Ukraine’s national treasures

As in many nations, some of Ukraine’s national treasures are their artists. One such artist is the writer, poet and playwright Lesya Ukrainka.

Ukrainka was born on the 25th February 1871 in the town of Novohrad-Volynokyi (now the city of Zviahel in the Zhytomyr Oblast). Her real name was Larysa Petrivna Kosach and she was the second child of Olha Drahomanova-Kosach and Petro Antonovych Kosach. The Kosachs were a family of Ukrainian nobles and activists, who were highly devoted to preserving the Ukrainian language and culture.

On the 18th May 1876, Tsar Alexander II issued a decree known as the Ems Ukase, which prohibited all publications in Ukrainian. It also banned Ukrainian-language theatre productions, public performances of Ukrainian songs and the language was banned from schools. In the 1880s, the restrictions were relaxed when plays and songs were removed from the list, but all the other restrictions remained in place. Fearful that Ukrainian in print could be permanently erased, Ukrainka’s father, Petro funded publications out of his own pocket.

Ukrainka and her siblings were educated at home by private tutors and their mother Olha in Ukrainian. Ukrainka also learned French, German, English, Italian, Greek, Latin, Polish, Russian and Bulgarian. She showed early signs of her writing talent when she wrote her first poem at 8 years old. It was her mother who pushed her towards writing and also taught her about feminism and the cause for Ukrainian culture. Olha would take her children on regular trips to the countryside where they could hear the peasants conversing in Ukrainian and singing regional folk songs, but to also admire the beauty of the rural landscapes. All this combined would shape the essential elements and themes of Ukrainka’s writings.

Larysa Kosach took the more apt pen name “Lesya Ukrainka” (“Ukrainka” means “Ukrainian woman”). Her first poem was published when she was 13 years old and in her career, she would write an impressive collection of poems, dramas and other literary and political works. She was a feminist writer who gave women a voice, a theme she especially touches on in her drama Cassandra, which retells Homer’s Iliad from the perspective of the tragic Trojan princess Cassandra. Needless to say, her works were also as a metaphor of the Russian Empire’s repressions against Ukraine and she became a strong activist for the language and culture, taking the risk to write her works and translating the works of others into Ukrainian, including Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s The Communist Manifesto.

Lesya Ukrainka left behind a legacy that shaped Ukrainian literature and culture. Unfortunately, her life was cut short by delicate health. She died on the 1st August 1913, aged 42, at a health resort in Sumari, Georgia. She is buried in the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv. On the 16th November 2022, the Pushkin Avenue in Dnipro was renamed Lesya Ukrainka Avenue.

“I’ve never been in love before, and I never knew, that love could be so sweet” - Lukash. Act 1 of The Forest Song by Lesya Ukrainka (1912)

The Forest Song

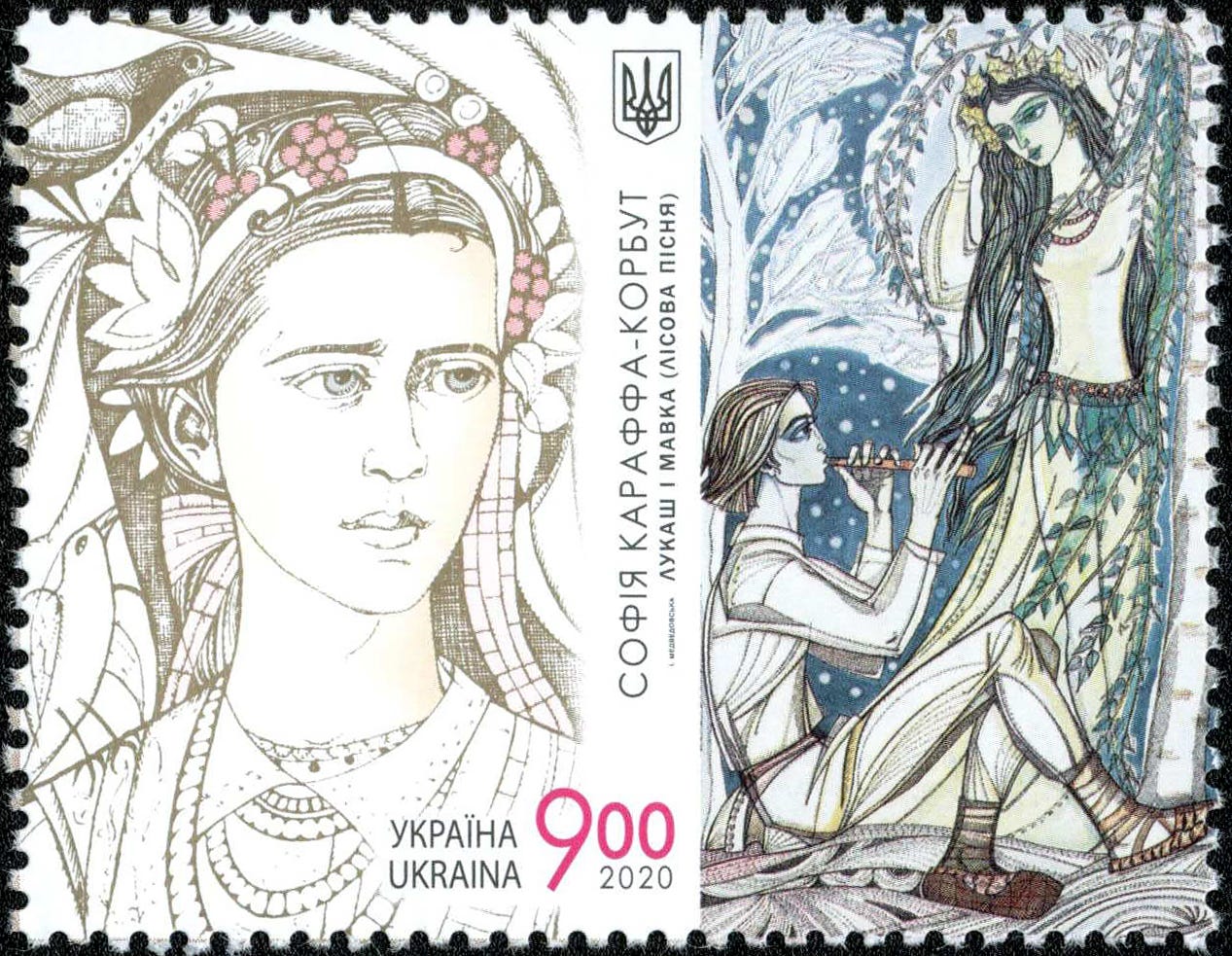

One of Ukrainka’s most famous work is her play The Forest Song, a work that can especially be read as a love letter to Ukraine. According to an article by W. Besoushko, “In The Forest Song Lesya built a monument to her country, with its beautiful woods and lakes and superstitions. The work deserves a Mendelssohn composition for accompaniment.”1 The story is a fantasy tale and a tragic love story between the forest nymph Mavka and the mortal man Lukash, which brings the worlds of mortals and the supernatural together, but, as in many romantic stories, all ends in tragedy.

As Besoushko states above, Ukrainka was inspired by the national forests and mythology, as she explained in a letter to her mother:

“It seems to me, that I just remembered our forests and longed for them. And then I have always kept that Mavka in my mind, for a long time, ever since you told me something about Mavkas in Zhaborytsia when we were walking through a forest with small but very dense trees. Then in Kolodyazhne, on a moonlit night, I ran into the woods alone (you didn't know that) and there I waited for Mavka to appear. And over Nechimne, I imagined her, as we spent the night there — you remember — with my uncle Lev Skulinsky. Apparently, I already had to write it once, and now for some reason, the 'right time' has come — I myself do not understand why. I am fascinated by this image forever.”

While Ukrainka’s play is rather unknown in the west, Slavic mythology is no stranger to the stage, appearing in several 19th century operas and ballets. The most famous ballet in which an element based on Slavic mythology appears is Giselle. Although the ballet is set in Germany, the wilis, the ghostly killer-brides, are based on the Slavic fairy maidens the vila and the samodiva. The legend of the vila also served as inspiration for Giacomo Puccini’s opera Le Villi. Another 19th century Slavic-themed ballet was Roxana, the Beauty of Montenegro by Marius Petipa that features not only wilis, but witches and vampires based on the variants from Eastern European folklore. There was also Mlada, a work given in various versions, based on the myths of the pagan Slavic gods. But perhaps best known in this respect is Antonin Dvořák’s opera Rusalka, which is based on the legend of the rusalka, a water nymph or fresh-water mermaid.

The principal character of The Forest Song is Mavka, a forest nymph. According to the myth, mavkas are similar to rusalkas in that they are the spirits of young maidens who died unnatural deaths. They are beautiful women with green eyes and long hair, but they have no skin on their backs so their internal organs and spines are visible from behind. The mavka appears frequently in Ukrainian folklore and culture: in some cases, she is harmless, while in others, she is malignant: like the rusalka, she can be deadly as she lures young men into the forest and tickles them to death.

Ukrainka wrote her play in the summer of 1911 and it was published a year later. She never lived to see her work in performance because it was staged in production five years after her death. The Forest Song premièred at the Kyiv Drama Theatre (now, the Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theatre) on the 22nd November 1918. The play has since been staged all around Ukraine. It was also adapted into two ballets, two operas, two full-length live-action films in 1963 and 1980 respectively, and an animated film in 2023.

Before looking at how The Forest Song became a ballet, I will go into an overlook into ballet in the early decades of the Soviet Union because it helps to understand how the art form developed in Ukraine.

In the 19th century, ballet was very popular in Europe, but it flourished the most in Russia by the artistic genius of the Frenchmen Jules Perrot, Arthur Saint-Léon and Marius Petipa. At the turn of the 20th century, the avant-garde began through the innovations of Mikhail Fokine, which manifested with the establishment of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. But after years of ballet as a theatrical art form that brought entertainment to its audiences, everything would change in that fateful year of 1917 and it was after this dark period that the Ukrainian ballet would be established.

Ballet after the 1917 Revolution (1919-1931)

In 1917, the fuse that set off the Russian Revolution was ignited. The Tsar was dethroned and murdered, and the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, declaring the beginning of a new socialist era, an era of turmoil and bloodshed. The arts and culture would get caught up in the chaos, especially ballet and from 1919 to 1922, it was the subject of an ideological debate. Radical party members questioned ballet’s right to exist, wishing to conform to a uniquely proletarian culture, but there were those who were firm supporters of ballet and who would repeatedly fight for its survival.

The demand was for the arts and culture to represent and reflect the socialist, realist ideologies of the Soviet Union. In other words, they were to be tools for Soviet propaganda. If ballet was to survive, it had to submit to the political pressure that was calling for the former imperial ballet to be reshaped into a Soviet art form. This was no easy task and the 1920s was a decade of choreographic experimentations as the ballet artists looked for ways to make ballet fit the Soviet mould.

From 1928 to 1931, an era known as the cultural revolution took place where new policies increased the ideological pressure on the arts. Ballets, operas and plays were categorised to determine which were suitable for the repertoire - those that were kept had to undergo change while others were banned. But in 1931, Joseph Stalin relaxed some of these policies, ending the cultural revolution and its militant call for proletariat dominance of the arts. Around the same time, a new ballet genre emerged - the drambalet, a genre that placed dramatic narrative at the forefront over music and dance, a genre of “danced pantomime” and “dramatised dance”, a rejection of the traditional, classical structure of Petipa with its removal of pantomime and large-scale divertissements. Basically, the drambalet was something of a danced play with music and no spoken words.

Of course, the drambalet was another tool of Soviet propaganda and by Stalin’s orders, it was the only acceptable ballet genre from the 1930s until the 1950s. Once Stalin slammed down his iron fist, the Soviet Ballet had to follow this policy - Petipa’s ballets and the other 19th century classics had to be “Sovietised” to fit the new genre. Any new ballets had to be created as a drambalet and the topic could be anything from classic literature and/or new stories. The earliest drambalets were Boris Asafiev and Vasily Vainonen’s Flames of Paris (1932) and Asafiev and Rostislav Zakharov’s The Fountain of Bakhchisarai (1934).

The policies that transformed ballet in Russia also served as part of the foundations that formed ballet in Ukraine. Ukraine declared independence in 1917, but this independence was short-lived and in 1919, a new Ukrainian Soviet government was formed that fought against nationalists. In 1922, Ukraine was absorbed as a founding state of the Soviet Union and became the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Any policies on arts and culture introduced by the Politburo applied not just to Russia, but to Ukraine and every corner of the USSR.

Ballet in Ukraine

Ballet first came to Ukraine in the 18th century through the serf theatres and throughout the 19th century, it mainly appeared across the country through visiting ballet troupes. In the early 20th century, several dancers from the Imperial Ballet toured the Ukrainian cities, including Anna Pavlova, Lyubov Egorova, Tamara Karsavina and Samuil Andrianov. Two prominent ballet artists worked in Kyiv on a long-term basis - Mikhail Mordkin from 1916 to 1922 and Bronislava Nijinska from 1915 to 1921. But it was not until after the 1917 Revolution that the Ukrainian Ballet was established.

The ballet company of Odesa was established in 1923 by the Italian Roberto (Robert) Balanotti, who staged Swan Lake for their première performance. In 1925, the ballet company of Kharkiv was established and for their première performance, Balanotti also staged Swan Lake. In 1926, the ballet company of Kyiv was established and the Russian ballet master Leonid Zhukov staged La Bayadère for the première performance. Zhukov was one of three ballet masters from Russia who went to Ukraine in 1926 to further establish the art of ballet there. In Kyiv, he also staged Giselle, Swan Lake and Don Quixote. The other two were Kasian Goleizkovsky, who went to Odesa, where he staged some of his own ballets - In the Sunshine and Joseph the Beautiful - and Vladimir Ryabstev, who went to Kharkiv, where he staged The Little Humpbacked Horse and Le Corsaire.

For the first decade of their existence, the Ukrainian companies’ repertoires were mostly made up of the classics, but in 1931, what has been labelled as the first “Ukrainian Ballet” was staged in Kharkiv on the 19th April. This ballet was called Pan Kanevsky and was based on a Ukrainian folk song. The composer was Mykhalyo Verykivskyi and the choreographer was Vasyl Lytvynenko. Though it was short-lived, Pan Kanevsky was the first step to bringing national-themed ballets to the stage.

In 1936, the year of the 65th anniversary of Lesya Ukrainka’s birth, it was decided that The Forest Song would be adapted into a ballet. However, the reasons as to why they chose The Forest Song are unknown. Many of Lesya Ukrainka’s works were banned in the Soviet Union, but The Forest Song managed to survive, probably because it is a fairy play and contemporary fairy plays were acceptable for stage productions under the criteria laid by the Soviet government. But to simply suggest that The Forest Song was selected as a new ballet because its genre met the Politburo’s criteria and because it is one of Ukraine’s most iconic literary works is too easy an explanation, especially given the timeline of events between 1931 and 1936.

From 1932-33, Ukraine was struck by one of its darkest chapters in the form in one of the most horrific genocides in world history - the Holodomor, a man-made famine caused by Stalin’s aggressive collectivisation of the agricultural sector, which starved millions of Ukrainian peasants to death. The famine also crushed Ukrainization, which Stalin, in his signature tactic to twist reality to shift blame from himself and the politburo, blamed for the food requisition failures. The Ukrainian Communist Party and the Ukrainian National Movement were mercilessly purged and there was a huge crackdown on Ukrainian culture and language. Various Ukrainian-language institutions - schools, universities and theatres - were shut down; newspapers and books were banned and replaced with Russian-language ones, and many figures of the arts, culture and educational fields were arrested, exiled, imprisoned and murdered; others committed suicide. The Ukrainian language was banned in favour of the Russian language and every Ukrainian had no choice but to speak, read and write only Russian. The Russification of Ukraine and hundreds of thousands of ethnic Ukrainians had begun.

Given the time of repressive terror that Ukraine had undergone and was still undergoing by 1936, the choosing of The Forest Song for a new ballet does not feel coincidental. A political and/or nationalist factor seems perfectly plausible because it strongly suggests that the Ukrainian ballet community wanted to prove that Ukrainian culture had not been destroyed. However, any information detailing how the opera houses, and the ballet and opera companies survived and operated in the 1930s, especially during the Holodomor and the Great Terror of 1937-38, is currently unavailable, so this is to be left as a separate study. For now, there is enough information that tells us about this most beloved Ukrainian ballet.

“In all the forest there is nothing mute” - Mavka. Act 1 of The Forest Song by Lesya Ukrainka

The Forest Song becomes a ballet

If Ukrainian nationalism was a key factor behind a ballet adaptation of The Forest Song, how and why was it approved? This information is still unavailable, but it seems that the reason for the seal of approval could have been Soviet propaganda. By the 1930s, the Politburo was using the arts as a propaganda tool to display Russia and the other satellite states of the Soviet Union as a supposed “brotherhood of nations”. In truth, it was all part of the cover up of Stalin’s crimes against Ukraine and the other states, so it seems that a Ukrainian-themed ballet was meant to work as the perfect cover for the genocide that had cast a dark shadow over the nation three years earlier.

The ballet score for The Forest Song was composed by the Ukrainian composer Mykhailo Skorulskyi. In her essay on the National Ballet of Ukraine’s website, Maria Zagaykevych writes that ‘Skorulskyi’s music has been described as full of “juicy orchestral colours” and “emotional fullness”. The score’s dominant features are “penetrating melody, lyricism and romanticism.” A significant element is Skorulskyi’s usage of Ukrainian folk songs, particularly the musical folklore of Volyn, as well as a musical embodiment of the deep experiences of the main characters.’2

The libretto was written by Skorulskyi’s daughter Natalia Skorulska, who was a ballerina at the National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine. Father and daughter set themselves the task of honouring and respecting the source material as much as possible, aiming to accurately capture the true meaning of Lesya Ukrainka’s work. They were determined that the ballet adaptation should do the play justice by producing emotional colour in the music and choreography, preserving the main images and plot elements, internal logic and dramatic development, in which reality is interwoven with fantasy. However, it proved impossible to adapt the play into a ballet without changes that would fit the ballet genre. Therefore, some episodes from the play were shortened, others were expanded, and new scenes were added, namely the scene of Lukash’s wedding to Kilina.

This scene follows the tradition of wedding scenes from other ballets where the heroine interrupts the festivities as her beloved prepares to marry her rival, which drives him mad, for example, James’s wedding to Effie in La Sylphide and the wedding of Gamzatti and Solor in La Bayadère. However, the scene also promotes the imagery of a happy village, presenting a romanticisation of Ukrainian peasant life. Ania Nikulina comments that several Ukrainian ballet librettos present the latter image and the motive was very likely to be political, seemingly a tribute to the millions of peasants murdered by Stalin.

The score was completed in 1936 and was accepted by the National Opera and Ballet Theatre as their newest work. Sergey Sergeev was assigned as choreographer, but there would be a long delay before the ballet could première. According to Zagaykevych, it was the outbreak of the Second World War that caused the delay in The Forest Song’s première. When the war broke out, the National Opera and Ballet Theatre was closed, and the opera and ballet companies and the ballet school were evacuated to Irkutsk and Ufa in Siberia. The première of The Forest Song would not happen until 1946, ten years after it was completed. However, the timeline does not add up. In 1937, the year after the ballet was completed, the Great Terror occurred, which saw the purge of many Ukrainian artists; the Second World War began in 1939 and the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

There is also the fact that Zagaykevych does not state when it was intended for The Forest Song to première - was it in 1936, the year of the 65th anniversary of Lesya Ukrainka’s birth? Or was it in 1941, the year of the 70th anniversary of her birth? Either way, it raises questions as to why Zagaykevych does not go into more detail and why she never mentions the Great Terror. The outbreaks of both the Great Terror and the Second World War would surely explain why it took ten years for the ballet to première.

Eventually, after the war had finally ended, The Forest Song received its world première at the Kyiv National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after Taras Shevchenko on, presumably, the 25th February 1946 (the day is not certain) during the celebration for the 75th anniversary of Lesya Ukrainka’s birth. The Prima Ballerina Antonina Vasilyeva danced the role of Mavka and the principal dancer Oleksandr Berdovskyi danced Lukash.

Since its première, The Forest Song has become one of the most prominent and celebrated ballets of the Ukrainian Ballet repertoire, with its topic promoting and epitomising national identity and culture. In 1958, the ballet was staged in a new production with new choreography by Vakhtang Vronsky, in collaboration with Natalia Skorulska. Vronsky’s production has since been revived three times at the National Opera and Ballet Theatre, first in 1972 by Skorulska. The second revival was by Valery Kovtun in 1986 and the third and final revival was Viktor Lytvynov, which coincided with the 120th anniversary of the birth of Lesya Ukrainka.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this was not an easy topic to research because of the lack of information regarding the history of The Forest Song ballet. But there are also many other missing pieces, namely the history of ballet in Ukraine at the time when the ballet was created. There are many areas in the field of ballet history that have yet to be researched and addressed, and the history of ballet in Ukraine is one such area. This essay reminds us that there is much to uncover here and it is my aim that this is the first step in that mission: to uncover more about the history of the Ukrainian ballet.

On a personal note, I dedicate this essay to Ukraine, to the people of Ukraine, to all in the Ukrainian ballet community, but especially, to my Ukrainian friends. I dedicate this to them as they continue to fight for their country’s freedom and as my friends in the ballet community continue to fight for Ukrainian culture. Their bravery, strength and resilience is so incredible, it’s difficult to describe in words, but I am so proud of them and so in awe of them; they are a true inspiration. I aim for this essay, future writings and projects of mine about the Ukrainian ballet to contribute to this cause. I stand with Ukraine all the way, I will keep giving them all my full support and I will do what I can to contribute to their fight for their nation’s freedom and their culture. Слава Україні!

“No! I live! I will live forever! I have a heart that does not die.” - Mavka. Act 3 from The Forest Song by Lesya Ukrainka (1912)

Appendix

Libretto of The Forest Song

Based on that written on the website of the National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine

Act 1

By a pond in a glade deep in the forest, as soon as the leaves on the trees have barely fluttered open, turning green, a group of mermaids emerges from the pond and dances. The water sprite known as He Who Rends the Dikes runs playfully and swiftly into the forest glade and embraces the head Mermaid, the daughter of the Waterman, begging her to run away with him. But her angry father is on guard and drives off the seducer, taking the naughty Mermaid to the bottom of the pond.

The villagers, Uncle Lev and Lukash come to the forest. Lukash carves a flute out of some reeds and plays sweet music, which stirs the inhabitants of the forest, and the forest nymph Mavka awakes from her winter sleep. She suddenly appears before Lukash to stop him when he intends cut down a white-barked birch tree and is struck by her beauty. However, Perelesnyk, the Fire Spirit appears and attempts to seduce Mavka, but she rejects his advances. Lukash returns and assists the frightened nymph. Lukash and Mavka fall in love, but the Mermaid and the forest imp Kutz appear and lure Lukash into the pond, but Mavka intercedes and saves him. Uncle Lev returns and Lukash introduces him to Mavka. Feeling uneasy, Uncle Lev tells Lukash it is time to leave. Lukash and Mavka kiss goodbye and Lukash leaves, leaving the forest nymph overwhelmed by feelings she has never known. The Mermaid and Kutz return with their fellow mermaids and imps and tell Mavka to forget the mortal, but Mavka’s feelings are too strong and when she finds Lukash’s flute that he left behind, she follows him.

Act 2

Mavka has joined Lukash at his home near the forest glade and they are planning to marry. However, Lukash’s abusive mother does not approve of the gentle Mavka and orders the young couple to get to work, chopping wood and harvesting wheat. She forces a sickle into Mavka’s hand, which saddens the nymph, and she makes her way to the wheat field. The Nymph of the Field appears with her fellow nymphs, and they implore Mavka to abandon Lukash and return to the forest. Although their company brightens Mavka’s spirits, she cannot forget Lukash.

Lukash’s mother brings in the young widow, Kilina, who is a very arduous worker. She berates Mavka for failing to work, but Kilina takes the sickle and harvests the wheat, much to Mavka’s distress. Lukash enters and his mother introduces him to Kilina, instructing him to help her with the harvest. Kilina entices Lukash and he cannot resist. Mavka witnesses all and is heartbroken. Perelesnyk, the mermaids and the imps appear, but all is interrupted by the demon known as He Who Dwells in the Rock, who reaches out his hand to Mavka. Mavka rushes to Lukash and imploringly looks into his eyes, but he spurns her. In desperation, Mavka throws herself into the arms of the monster and heavy boulders seal her away.

In the village, the villagers to celebrate Lukash and Kilina’s wedding. There is much merriment in the air, but during the celebrations, a vision of the despondent Mavka appears to Lukash and he is overcome with horror at his betrayal. Leaving Kilina and the guests, he flees into the forest.

Act 3

The forest creatures take revenge on Lukash for his betrayal, and he loses his reason. By the powers of her love, Mavka breaks free from the rocks that imprisoned her and comes to her beloved. Upon seeing her, Lukash falls at her feet, but the shame of betraying his wife drives him away. Kilina emerges from the house and encounters Mavka. She curses her rival and Mavka transforms into a willow tree. Terrified, Kilina flees back into the house, but her son cuts a flute from the willow. Lukash returns, exhausted, and his stepson asks him to play his new flute. Magic sounds pour out in which he hears his beloved’s voice again. Angry, Kilina tries to make Lukash cut down the willow, but he refuses, so Kilina swings the axe herself, but Perelesnyk appears and protects the willow. He sets fire to Lukash’s house and Kilina, her son and Lukash’s mother run away, Lukash, forgetting everything in the world, plays the song of lost love on his flute.

It begins to snow. Like a magical dream, Mavka appears to Lukash; her soul speaks to him, and they reaffirm their love. The snow covers Lukash, and he freezes to death while the spirit of Mavka gazes at him lovingly before she disappears.

Sources

Lesya Ukrainka, The Forest Song (1912). From the original publication Spirit of Flame: A Collection of the Works of Lesya Ukrainka. Translated by Percival Cundy (1950)

The National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine website - Repertoire - The Forest Song

Christina Erzahi, Swans of the Kremlin: Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia (2012). University of Pittsburgh Press & Dance Books Ltd, Pittsburgh, PA/Hampshire UK

Daily JSTOR - Lesya Ukrainka: Ukraine’s Beloved Writer and Activist

Wikipedia - Lesya Ukrainka, The Forest Song, Ballet (pages in English and Ukrainian)

Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine (2015). Penguin Books, 2016 ed. UK

Anne Applebaum, Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine (2017). Penguin Books, UK

Elizabeth Souritz, Soviet Choreographers in the 1920s (1979). 1990 ed. Duke University Press, USA

For those interested in ballet, a poem I wrote.

https://tonyholloway.substack.com/p/terpsichore?r=55ufbu